Listen Now

Chapter Overview

Chapter 1: AudiobookHub Recommendation

Chapter 2: — 3:13 A.M.: The Weight on His Back

Chapter 3: — Shame, Small Slights, and Heavy Stones

Chapter 4: — Stories the House Hides

Chapter 5: — Fights, Rhymes, and the Cost of Toughness

Chapter 6: — Living Inside a Beat

Chapter 7: — What Are You Escaping?

Chapter 8: — The Badgers in the Water

Chapter 9: — Eve, Badgers, and Broken Windows

Chapter 10: — Arms Around His Shoulders

Chapter 11: — Start Again at Dawn

Description

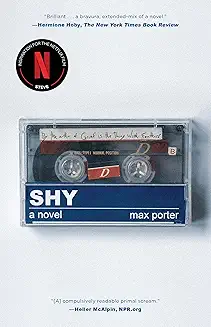

Shy is a night-long plunge into the head and heart of a troubled seventeen-year-old living at the Last Chance, a residential school for boys who’ve run off every other road. Across a single dark walk—hood up, Walkman clamped to his ears—Shy carries a heavy rucksack, and an even heavier load of guilt, impulsiveness, and urgent hope. He thinks about jungle music, about fights and friends, about a mother who loves him and a stepdad he resents, about therapists who are kind and patient, and about ghosts who might be real. There are sharp memories of broken bottles, screwed-up chemistry labs, and the small, humiliating moments that stick like burrs. There’s tenderness too: hugs in corridors, a day at Durdle Door, a bad joke that lands and makes the room laugh.

As the night widens, the house breathes with its layered history—kids and kings, myths and monsters—and the field feels close and huge at once. The ha-ha keeps animals out, but it can’t keep out fear, or need. Standing at the pond, spliff in hand, Shy sees something he cannot explain and something he understands too well: dead badgers floating like unanswered questions. What he does next—what the boys do next—turns the night into a bright, chaotic morning and proves a quiet truth. However messy and violent the story gets, mercy can arrive like a rush to the lawn. The book moves like a mix: spikes, breaks, breath, basslines, and sudden silence, all wrapped around a simple, human beat. A boy wants his mind to stop hurting. The people around him want him alive.

Who Should Listen

- Listeners who love raw, voice-led fiction that feels live and intimate

- People interested in youth mental health, care, and group dynamics

- Fans of music-driven storytelling and coming-of-age narratives